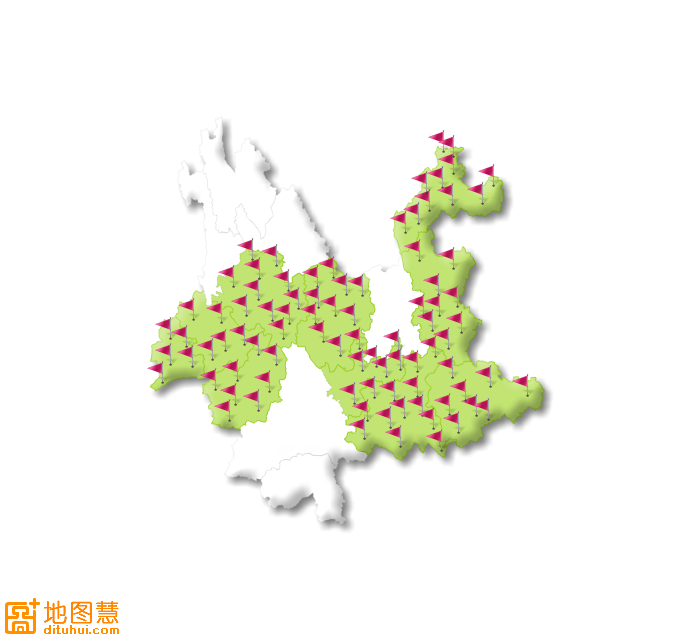

Newborn Congenital Heart Screening Training and Evaluation ProgramThe Yunnan Newborn Training Program has the goal of training all rural Yunnan county obstetricians and obstetric nurses to perform proper newborn cardiac examinations. The program, started in 2014, is the largest of its kind in China and one of the largest of its kind in the world.

Part I. Yunnan Newborn Training Program DescriptionIntroduction In 2014, China Cal and the Kunming Medical University formed a steering committee with the purpose of executing a program whose purpose was to train rural Yunnan personnel responsible for the care of newborns how to properly examine their hearts for congenital heart disease using pulse oximetry and stethoscope. This committee had the following responsibilities:

Beneficiaries of the Training Program: Newborns in rural Yunnan Objectives of the Training Program The objectives of this program are:

Support and Staffing This training program is supported by the Ping and Amy Chao Foundation and by the Masimo Corporation and by the general fund of the China California Heart Watch. The program presently has the following paid staff.

Daily Protocol Routine

Part II. Training Activities Since December 2015

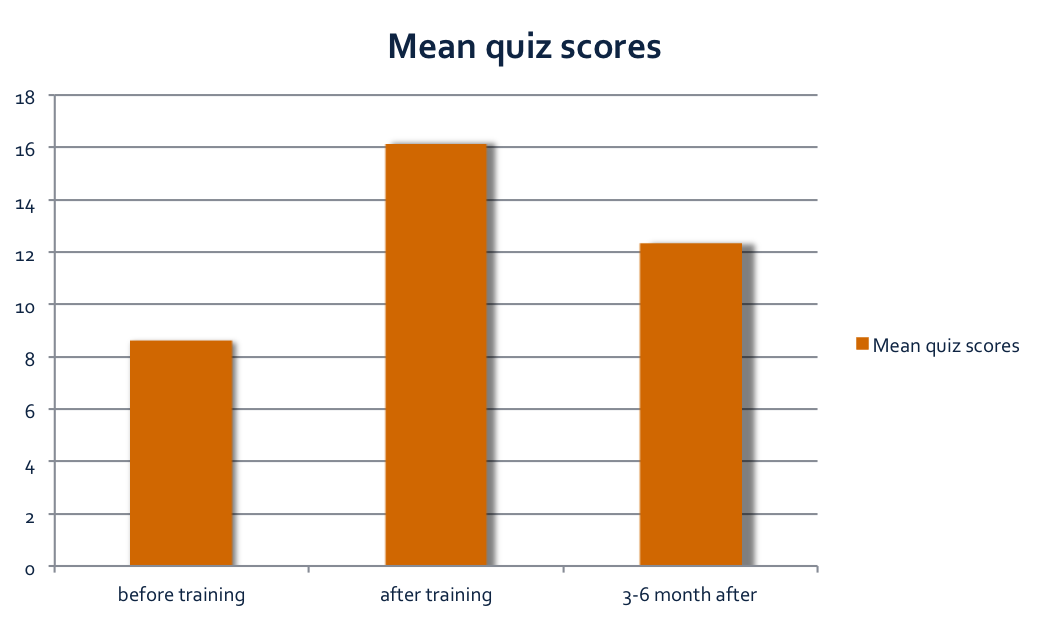

Part III. Progress in Evaluation of TrainingOn June 13, 2016, Fangqi Guo presented the following data to her PhD advancement committee at the University of California, Irvine. The committee questioned her for two hours and made suggestions. At the end of the meeting, she was advanced to candidacy. The following summarizes her data.

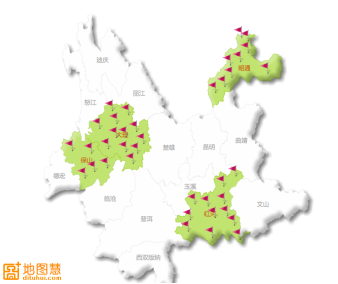

Since the trainees were first introduced to pulse oximetry at our training session, behavior scores for this skill were zero at baseline. Notably, 79% of the trainees showed proper use of the oximeters three months after training. The 2nd table shows marked improvement in the use of stethoscopes 3 months after training. Screening Rate, Echo Rate and Case Findings The training was intended for all 125 Yunnan county hospitals. The evaluation is limited to sufficient county hospitals so that at least 300 doctors and nurses would be trained and their knowledge and behavior evaluated and at least 13,000 newborns would be screened using estimates of birth rates from past years. Since birth rates increased beyond that expected during the last quarter of 2015 and continue to increase in 2016, we expect approximately 24,000 instead of 13,000 births in the evaluation part of our program.

September 2015 to May 2016 Screening Rates

The rates in all prefectures are between 91% and 98%, which far exceed our expectations. However, there is, hidden in the low not screened rate, a significant bias problem. This is what we call the “too sick to screen” problem (Problem 2 below). Nurses and doctors noted some newborns to be very ill with cyanotic skin color, breathing shallowly and otherwise showing signs of clinical distress. We discovered, after a telephone survey, that these very ill newborns were often not screened at all but instead were referred to the pediatrics department or transferred immediately to a larger hospital. We suspect that a high proportion of these “too sick to screen” newborns had critical congenital heart disease. We intend to request birth/medical records from the birthing hospitals in order to retrieve diagnosis and pulse oximetry results. (See below Problem 2.). Abnormal Rates and Case Finding The table below shows the abnormal rate and the ultrasound exam rate (echo rate) for abnormal screened newborns and the number of cases of congenital heart disease (CHD) and critical congenital heart disease (CCHD) that we found. We had hoped that all abnormal screened newborns would undergo ultrasound examinations. Instead, the echo rates shown in the last columns shows that less than half of the newborns with abnormal screening exams underwent ultrasound examinations. See Problem 1 below. The overall case finding rate was also lower than expected. In western populations and in a large study from Shanghai, case finding rates of critical congenital heart disease are about two per thousand. We found only four cases which represents a much lower case finding rate. See Problem 3 below.

Part 4. ProblemsWe have encountered three problems, alluded to above during the execution of this program. Problem 1 The percent of abnormal screens that undergo ultrasound (Echo Rate) is low (48%). This means that most infants with abnormal screen results (who have a high probability of having serious heart disease) are not receiving diagnostic ultrasound exams. We have taken some remedial measures, listed in our last progress report, to correct this problem but the echo rate remains low. We telephone canvassed the newborn champions at all of the hospitals in the evaluation program. From this phone canvassing, we have discovered one important cause of this low echo rate problem may be that the insurance reimbursement policies of the various counties vary. In some counties, newborn infants are counted on their mother’s insurance and are therefore covered for exams like cardiac ultrasound. In those hospitals, echo rates tend to be higher. In other hospitals, newborns are considered “out-patients” as soon as they are born and are therefore not reimbursed for diagnostic tests. They can be reimbursed for their ultrasound examinations only if they are transferred to pediatric in-service. Proposed Solution to Problem 1 We will do the following:

Problem 2 Newborns who appear in “distress” (breathing shallowly, cyanotic, low APGAR) are often not screened by our protocol but instead are rapidly transferred to a larger hospital facility or to another department (pediatric NICU). These newborns are few but extremely important as they fail to benefit from the screening program which provides a path to life saving treatment at a large medical center. This also presents an important scientific problem for our evaluation. These newborns who are “too sick to screen” will create a bias of unknown size since the number of cases of CCHD will probably be high in this group. Proposed Solution to Problem 2 During the months of August through October, we are planning to recover some or all of these lost data. We will do this by sending a small team to all hospitals to request viewing and recording of data from medical records of those infants who were not screened. This amendment to our protocol has already been approved by the UCI Institutional Review Board (IRB) and a volunteer, Ms. Kristina Hwang, has agreed to assist Ms. Guo and Ms. Zhang during these three months. The cost of this will be quite low and we will not require additional funds. However, we can use the results of this amendment to design a better evaluation to follow this one in 2017. Problem 3 Of the four cases of CCHD identified, only one (Baby L) agreed to undergo curative surgery and has already undergone a temporary palliative operation (Blalock Taussig shunt) and will return to West China Hospital in two months for a definitive operation or cure. We called the families of the newborns who refused surgery in order to determine their reasons for not following through. Lack of trust in the health system appeared to be a strong barrier. The one infant who underwent surgery and survived was Baby L, a male infant with pulmonic valve atresia born in Mi Du County. This baby’s family also refused operation until China Cal staff intervened. Mi Du County is sufficiently close to China Cal headquarters in Da Li so that it was possible for two staff members and I to travel to Baby L’s place of birth to speak with his family. After carefully explaining to the family the gravity of his illness, the treatment options and the state insurance and charitable help available, Baby L’s mother agreed to surgery at Chengdu West China Hospital. Baby L underwent surgery in May and is now home and waiting for the second part of his two-part operation. Baby L’s case demonstrates that impoverished families need professional counselling by a patient advocate whom they can trust and who can explain treatment options and available financial assistance. Our training program needs a better way to communicate with families. Proposed Solution to Problem 3 We will adopt a patient advocate system using a local Yunnan physician in the capital city of Kunming and using video-communications between advocate and families. We will use smart phones with video communications software. The advocate, a native speaker of Yunnan dialect, will explain to the family options and assistance available in order to save their infant's life. The advocate would help the family navigate the insurance system, get grants and arrange transportation to a surgical facility in Kunming. The patient advocate will increase the "save rate" from zero to over 50%. Plan for Remainder of 2016 By the end of August 2016, we will have completed training in 10 of the 16 Yunnan Prefectures and we will have collected almost all data for the evaluation of our training program. We will still have 6 prefectures which will remain untrained. They are De Qin, Nu Jiang, Pu Er, Xi Shuang Ban Na, Li Jiang and Kun Ming. If we train one prefecture a month, we can complete four of these by the end of the year. Written by Robert Detrano, July 2016

Comments are closed.

|

TFISH FUND BLOGWe update news and reports directly from the field written by our NGO partners daily. Top PostsPHOTOS & VIDEOSIN THE NEWSCategories

All

Archives

August 2017

|

|

© Copyright 2011. All rights reserved.

171 Main St. #658 , Los Altos, CA 94022 | [email protected] | 501(c)(3) Tax ID: 45-2885139 |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed